Columns

DEFINITION: A vertical element with a capital and a base. Columns are architectural structural elements that may support the weight of the structure above, or they can be purely decorative.

Ref: A History of Architecture

The employment of columns is the greatest step towards bringing the architecture of the entablature into a definite and artistic form. It is manifest that when anything like a series of openings is required, it is not sufficient for them to consist of mere breaks in a continuous wall; the eye requires some more graceful and finished support than the masses of masonry left by such a process. The column is the appropriate substitute, and we consequently find it in use even at a very early stage of the art. The facts recorded in the last chapter leave no doubt of the extensive use of columns in the architecture designated as Pelasgian; not only has a fragment of a highly enriched one been discovered, but the employment of a column as a merely decorative feature over the Lion-Gate at Mycenae seems to prove still more.

Lion Gate at Micenae. It was erected during the 13th century BC

The entablature undoubtedly, and probably the arch also, has been invented several times in distant corners of the world. And as nations come upon the stage of history at different periods of the world's existence, as the political and social infancy of one coincides with the old age of another, so is it with their progress in the building art. The Egyptian structures, to be hereafter treated of, have probably stood for more years than any that will be mentioned in the present chapter; nevertheless they do not exhibit the art in the same early form, but in one very much developed and enriched. We have already observed to how great an extent each style of architecture retains the character of the material in which its first examples were constructed :—a fact of itself sufficient to prove their independent origin. But the column, in some form or other, pervades all; the cave, the tent, the wooden hut, alike develop into it; each leaves its impress upon some of its numerous varieties. The column indeed is the most natural shape for any attempt at an ornamental support; a decorative imitation of a trunk or a tent-pole could hardly assume any but the cylindrical form; and when the rock was hewn out, or when the mass of wall between two openings began to be reduced into more graceful proportions, the same form is equally the most natural for such a diminished mass to assume. It might, indeed, at first be square, but beauty and convenience alike would suggest chamfering or rounding-off the angles, and by this process the genuine column is at once produced. The capital and base are such natural finishes, that they could hardly fail soon to be added, and that without doubt at a much earlier stage of a style originally stone, than in those which are to be traced up to erections of timber. Such an one, as we shall hereafter see, is the architecture of Greece; the earliest form of its column was a post driven into the ground or floor; consequently a base for it to rest on could have no place until the original type was somewhat obliterated. We consequently find that the simplest and purest of the ancient orders is worked without that feature. Similarly in the Chinese architecture, which reproduces a tent just as the Grecian does a hut, (though an apology is due to the shades of Pericles and Pheidias for mentioning the two in one sentence,) the capital is wanting, the wooden pillar being actually pierced, as in the original construction, by the beam, which must in courtesy be looked upon as an entablature. In an original stone construction, whether of erection or excavation, there would be nothing to hinder the introduction of features so needful to complete the finish of the whole, and to effect a due cohesion between the several parts. The extensive ruins which late researches have brought to light in central America, will afford as good a notion of a very early stage of columnar architecture as any monuments which have been preserved. Their history, and that of the race by whom they were erected, is shrouded in impenetrable darkness. Of the fragments recorded in the last chapter we have indeed no cer¬tain dates, no records on which we can implicitly rely, but we have at least legend and tradition to occupy their place. If we cannot repeople them with their real founders and inhabitants, we can at least people them with those whom successive ages have regarded in that light; at all events we have, or suppose that we have, a tolerably correct general notion of the race, language, and social condition of those who reared them. But here all is midnight: the structures themselves exist, but their authors are as though they had never been. Not only their history and institutions, but their very race and name have vanished; and the imagination is left to wander unrestrained among the mighty fragments of an unknown world. Many deep thoughts might be raised in the breast of the poet or the moralist, at the contemplation of these sumptuous structures now untrodden by the foot of man, but which may perchance have once rivalled the wealth of Sardis, or Babylon, or Persepolis, cities which have perished with them, but have left a name behind. The ruins however do not say much for the state of art among the people, whoever they may have been, to whom they owe their origin. They are essentially barbarous, and like all barbarous structures, seek to supply by cumbrous magnificence and superfluous ornament, the want of the higher beauties of grace and proportion. And we cannot fail to remark, even at the onset, that the same system of ornament which everywhere marks this stage of art is found here in great abundance. The ubiquitous chevron, which we have already seen at Mycenæ, meets us again at Uxmal and Chichen, where the presence of the followers of William the Norman is no less problematical than in the halls of the Atreidæ. The general notion conveyed by these remains is decidedly that of a stone construction, although some of the details appear to point to a wooden origin. There seems indeed no absurdity in supposing a simultaneous employment among a rude people of the cave and the hut ; and if so, the ideas borrowed from the two constructions would doubtless be intermingled in their attempts to bestow somewhat of an ornamental character upon their buildings. Many of the larger erections exhibit long and rich façades with many columns, but the genuine colonnade hardly occurs ; the columns are merely incidental, not occurring in continuous ranges, but merely here and there, just as one or two openings were wanted, which might be most conveniently treated in this manner. The wall is the essential feature ; the intercolumniations, if we may dignify them with such a name, are merely certain of its apertures, which happen to be divided by a column instead of by a mere mass of wall. The two modes of division are used in the very same façade, and other fronts occur without any columns, none of their openings having advanced be¬yond the character of doorways. The entablature too, if it may be so called, is preposterously heavy, and its form is in no degree influenced by the pillars below, or regulated by their proportions. It occurs indeed equally whether its supports are columnar or not. This might almost look as if the arrange¬ments of a colonnade had been transferred to a wall, as in so many façades of Italian architecture, yet the whole appearance of the style seems to countenance the idea of an original mural construction. The notion is rather that of a continuous mass, occasionally interrupted by apertures and pillars, than of the genuine portico, where the columns are conceived as first existing, and the entablature as laid upon them. Of course such a style as this does not employ a feature so essentially wooden as the pediment; and thus additional heaviness is procured. How different is all this disproportion and confusion from the perfect and harmonious symmetry which pervades the simplest Doric temple. And in the details the same unskilfulness prevails throughout, its only disguise being the lavish employment of every kind of uncouth and barbarous enrichment. The columns by themselves might recal for a moment that glorious conception of simple unadorned majesty, the uncorrupted Doric; but it is only in simplicity that they agree, and simplicity without grace is mere rudeness. These pillars are mere perpendicular masses, not only without fluting, which may be excused, but without any diminution of diameter. Some of the ornaments, as was before said, seem to bear about them traces of a timber origin, being very like what we see among ourselves in summer houses and such like structures of wood, where ranges of small cylindrical logs are placed close together. Some of these are furnished with what may be called bases, capitals, and bands; though their air is rather that of an elongated baluster than of a genuine banded shaft. But the circumstance of most real interest connected with these ruins is, that while the arch does not occur in a pure state, far less enter into the decorative system, we find the same at¬tempts at it which we have traced among the early inhabitants of Greece and Italy. It is certainly most remarkable to see exactly the same process, the same strivings after the ad¬vantages of an arched construction, going on in two such distant regions, where the idea of borrowing one from another is altogether out of the question, even were it not antecedently precluded by the improbability of a mere fruitless experiment being imitated. These, and other instances which we shall have to mention, show that architecture is in most countries a plant of indigenous birth, and has everywhere passed through the same, or at least analogous, stages. The want of the arch was almost universally felt, though it was not every nation that had the ability, or the good fortune, to bring their endeavours after it to a successful issue. Such at least was not the case with the people of Yucatan, who seem to have remained at even a greater distance from success than the old Pelasgians. The form most usual in their structures is an opening with inclining jambs, straight or curved, not joining in a point, though approaching very nearly to it, but with a lintel laid across the top. This mode of construction is here, as well as in Greece, applied to the erection of quasi-vaulted roofs. In other cases the roofs are supported on square pillars. From these remains, which, rude and uncouth as they are, are not without interest, both on architectural grounds, and from our very ignorance as to their history, we will turn to the oppo¬site quarter of the globe, and take a brief view of the architec¬ture of the nation which may fairly lay claim to a greater antiquity and an earlier civilization, than any other now existing as a distinct people. Not that there is any resemblance whatever between Chinese and primitive American architecture; but simply that it is a convenient arrangement to dispose of these forms of less beauty and importance, before we commence the series which will lead us by a gradually ascending scale to the full glories of Poseidonia and of Athens. The buildings of the celestial empire have but very little claim to architectural beauty or propriety; and in this case, as in all the other institutions of that extraordinary race, it is not owing to mere rudeness and barbarism, but to a fixed depravity of taste. Their erections are not the huts of savages, but the dwelling-places of a people whose civilization is older than that of Greece or Italy, and whose architecture, like their other arts, laws, and manners, has stiffened for thousands of years in the same mould of rigid immobility. China seems to occupy in the modern world a position analogous to that of Egypt in the ancient; both nations up to a certain point had made greater and more rapid advances than any other people, and had from some unknown cause become fixed at that point for ever. The two civilizations were probably contemporary, and that the Egyptian has not been handed down to our own days as a living system, as well as the Chinese, appears to be wholly the result of external circumstances. The Chinese are acquainted with the arch, and use it in their bridges; and, when we consider that they alone possessed for ages three of the great discoveries of modern Europe, there is no improbability in supposing that they boldly threw it over their great rivers in all its mechanical perfection, before the Pelasgian builder had even ventured to make his overlapping stones pre¬sent some feeble approximation to its outward form. But they have never made it a decorative feature, nor does it seem to be at all introduced into those structures which are designed to be ornamental, with the exception of what are called triumphal arches, though their claim to that title is not always very valid. The general outline of Chinese buildings is tolerably familiar to us: the manner of building in stages, often diminishing in size, and each furnished with a roof and balcony, as well as the extraordinary hooked form given to the angles of the roofs. This is found both in the larger houses and in the towers or pa¬godas. These erections can certainly make no claim to the smallest share of beauty; indeed their outlines must be consi¬dered as positively ugly, and the bright colours and decorations in which their builders delight must be but a poor substitute for graceful composition and harmonious proportions. The columns employed by the Chinese have been incidentally mentioned in a former part of this chapter. They are com¬monly of wood, fixed on stone or marble bases. Their being pierced with the beam most incontestably proves their direct1 origin from the tent; such an arrangement would never have occurred in an original stone architecture, nor yet in the reproduction of a timber hut. Their height is from eight to twelve diameters; and they gradually diminish towards the top. Their bases exhibit a variety of profiles, but none of any great elegance. Another form of architecture in Eastern Asia presents some analogy with the Chinese, though with considerable diversities. These are the buildings of Siam y2 whose outlines partake of the same character as the Chinese, so far as that both possess that re¬markable pyramidal rising of the whole structure to a crowning and, as it were vanishing, point. But instead of the balconies and curling angles of the Chinese roofs, the Siamese struc¬tures display a profusion of peaked roofs and gables. When a number of the latter, gradually ascending, encompass a sort of spire perched on the ridge, as is sometimes the case, the outline, barbarous as it is, must be confessed to be something very superior to anything in Chinese architecture. On the other hand a high roof over a colonnade, which is also seen, must be confessed to be not a little out of place. The outward resemblance which the religion of Buddha bears to some of the doctrines and ceremonies of the true faith, (rendering it thereby a more thoroughly hostile system than any other false worship,) has been often remarked, sometimes with evil purposes. But it may be allowable to compare the undoubted fact with the circumstance that some features in the Buddhist temples of Siam present an exactly similar resemblance to the architecture of the Christian Church. The gables just mentioned may be considered as an instance; and it is still more strikingly shown in the sacred spires. These are of divers forms and outlines, but all of the same aspiring tendency, and all seem to cry aloud for the cross as their natural finish. The most remarkable is that of a temple called Wata-naga, which in its general outline most vividly recalls the appearance of such erections as the Eleanor crosses or the market cross at Winchester, its open character assimilat¬ing it more closely to the latter. But upon examination it will be found, as I have heard it expressed, literally living with demons. Pointed arches, or their appearance, occur in two stages, but the lower range, as if in direct mockery, are actually formed by the extended legs of some monstrous portent of de¬praved idolatry. If Buddhism really be a Satanic burlesque of our religion, one might be almost tempted to consider such erec¬tions, of the age of which I can give no information, though there are reasons2 for supposing none of the Siamese buildings to be very ancient, to be in truth a similar burlesque upon Christian architecture and Christian emblems. All these structures, Chinese and Siamese, show a very low state of real art. Mere rudeness in execution is a necessary stage in its development among any nation, and does not exclude majesty of proportion, or even a kind of beauty; but we here see a manifest attempt at architectural splendour, without any per¬ception of beauty whatever, but with a taste thoroughly depraved alike in composition, detail, and decoration.

Columns in Antique Architecture

Ancient Egypt

There are two types of colums with 30 different forms that have been isolated from ancient Egpyt temples.

The first type are polygonal columns which, over a period of time, increased its number of sides from four to sixteen. The second class are stone imitations of plants such as the papyrus, palm and lotus.

papyrus campaniform column, Karnack

Lotus column, Karnack

Palmiform column

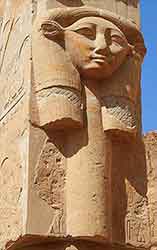

Hathor column, Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri.

Complex form column, Edfu

Papyrus column, Saqqara, Egypt

The type and form of column was often dictated by its placement within the temple, and therefore most temples actually employ more than one design. Most of the time, "Bud" style columns were used in the outer temple courts, particularly away from the central axis of the inner temple. "Open" style capitals were most often found in the temples' central areas.

Greece

Doric Column

The Doric column varies in height from four diameters to six and a half, the measurement being taken at the base. The older examples, as the temples of Zeus and Hercules at Agrigentum, are the most massive, having the intercolumniations small, and the entablature proportionably heavy. The base is never added; the post driven into the ground had no means of suggesting such a finish; and besides this, the omission would seem alto-gether in the spirit of the style. The capital is equally simple, and is wonderfully effective. It is a simple ovolo under a plain, square, heavy abacus, a genuine tile, without moulding or orna¬ment of any kind, which preserves most strictly the character of a distinct member rather than a mere finish to the capital, and calls to mind some of our own Romanesque abaci.