The Romans had deities under whose care were supposed to be the lintel, hinges, and other parts respectively of the door, and who were thence called Limentinus, Cardea, Forculus. Vesta was considered the tutelary guardian of the limen. There were numerous ancient ceremonies connected with doors. The sills seem to have been the part more particularly the object of reverence to the romans, and were frequently kissed by those entering or departing. it was also considered particularly unfortunate to tread with the left foot on the sill. Vitruvius in his third book does not consider it beneath the dignity of his subject to define the number of the steps leading to a temple or house, so as to ensure that those, who entered, should tread on the sill with the right foot and not with the left, which they held to be peculiarly ominous. To the doors of temples, palaces, and even private houses were sometimes affixed arms, spoils, and military rewards, as is evident from numerous passages in Virgil:" Barbarico postes auro spoliisque superbi Procubuere."

Crowns and festoons of flowers were frequently attached or suspended from the doors of public edifices, and indeed of the private dwellings of such, as took particular interest in the celebration of any festival, and also in seasons of public rejoicings or occasions of private festivity or grief.

Among the Romans the cypress indicated the door of a dwelling in which the defunct lay, and warned strangers from the unpropitious threshold. Mazois in his Palais de Scaurus notices a popular superstition of the Romans, which he applies to Scaurus, whom he represents as influenced by the idea, that a magician had buried the head of a dragon under the sill of his palace door, and to which he ascribed the property of his family. Visions and nightly horrors were supposed to be efficaciously kept away by a nail taken from the sepulchres being driven into the post or sill.

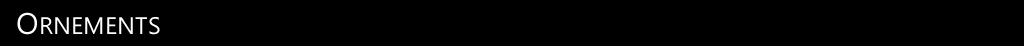

This door forms the entrance to the spiral staircase of the Trajan column,, which, commencing at the pedestal, leads up to the summit of the capital. It is a simple architraved door, agreeing in its proportions very nearly with the Vitruvian rules. The base mouldings of the pedestal are cut straight through, instead of being returned in profile to receive the moulding of the architrave. It is probable that the inner door itself was anciently bronze: the present one is evidently modern.

It was not unusual to inscribe upon the doors, jaumbs, or lintel some sentence describing the nature of the place, or impressing some moral maxim on the mind of the beholder.

The care of the entrance was confided to a slave, who was summoned by striking the door with a knocker,the room he occupied was called “ cella ostiarii” or “ janitoris.” The duties of this slave, in addition to his care of the sacred fire kept in every dwelling and of the lamps burning before the statues or images, was to answer to those of outoor porters and to guard against the intrusion of importunate or unwelcome visitors, or the admission of robbers during his absence, he had a dog or two. An interesting mosaic, found in the House of the Tragic Poet at Pompeii, represents a dog chained, as if about to spring upon the intruder, with the words “ cave canem” inscribed under him.

The Romans wanted to receive their friends and relations with every demonstration of welcome. The hospitable salutation of SALVE inscribed on the wall, traced in mosaic on the sill itself, or worked on the pavement immediately within the porch, offered a propitious omen to those, whom they held in particular regard. Frequent instances of this custom occur in the Houses of Pompeii.

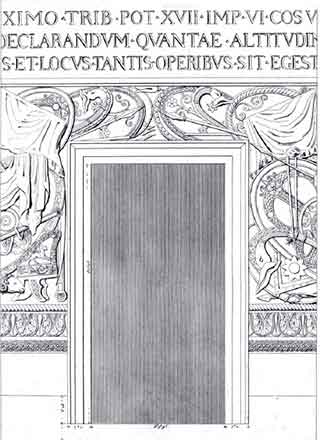

Doorway from the temple of Romulus, Rome. The temple was built in the early 4C

It would appear, that sometimes the doors consisted of four leaves, whether this meant two in height and two in width, or whether they were all in the width, it is impossible to determine, although some grooves and sinkings in the sill of the entrance to the House of Actaeon at Pompeii indicate the doors to have been four-leaved in width. They were usually framed in various kinds of wood, as cedar, elm, cypress, oak, etc. Some were of marble, iron, others of brass.

As noticed by noticed in Donaldson’s Pompeii, “ The door is about three feet high, two feet nine inches wide, and four inches and a half thick, and turns upon two bronze pivots, which work in sockets of the same metal; there was a metal handle to draw it to, and it was fastened by a lock, the traces of which still remain.”

From Cicero (orations against Verres) we know that there was doors ramed of some valuable hard wood, and inlaid with panels of classical compositions, sculptured in ivory, and enriched with gold.

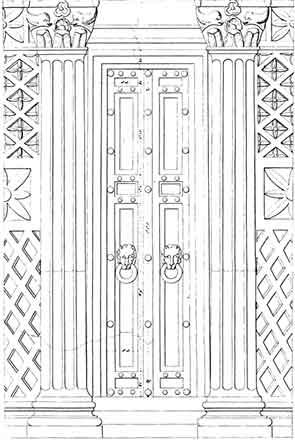

Door from

an antique alto-relievo (it once belonged to Sixtus Quintus, and came out of his villa Negroni.)

The hinges of the oldest buildings were made of wood, elm being considered the best, as we learn from Pliny : “ Rigorem fortissime servat ulmus ob id cardinibus assamentisque portarum utilissima, quoniam, minime torquetur : permutanda tantum sic, ut cacumen ab inferiore sit cardine, radix superiore:” However hinges were often made of brass or bronze as the one kept at the British Museum.