IN architecture the Tudor period covers a wide space of time and many varieties, though it possesses a well defined general character. In its earlier stages, which may, indeed, be traced as far back as the middle of the 15th centuryt. We may see in it the result of an intellectual as well as a material revolution, an awakening, for it marked the rapid decadence of feudalism, the spreading of the base of social stability as a result of the growth of the city, the rise of the petty gentry and the greater prosperity among the yeomanry.

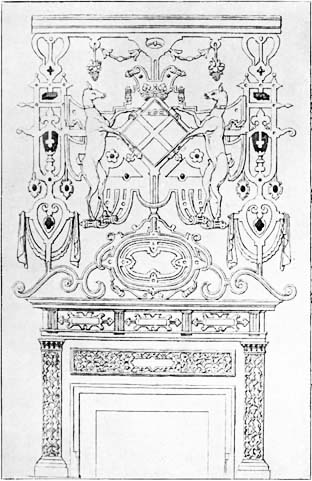

Our first example is from Weston Hall, Warwickshire, and Is dated 1545. It is a great structure, 13 feet 6 inches high, of carved oak. The jambs are tapering Ionic pilasters, moderately carved, support'ng an elaborate entablature. The frieze is supported by long, tapering Ionic pilasters, placed on high pedestals. These pilasters are carved with foliated ornaments and the family crest, a sheldrake. The frieze, which is divided up Into arched panels by a series of small caryatides supporting a continued cornice, is adorned with portraits of courtiers of Henry VIII. Over the lintel are two recessed arched nichcs and an armorial shield. The general design 3 classic, but the detailed decoration distinctly Tudor. The fireplace furniture belongs to a much later date. This use of armorial insignia and of portraits connecting the owner with his particular duties in life are quite characteristic of the age, and show the important position occupied by fireplaces in the social economy of the time.

Many of these “storied ’ chimneypieces have a genealogical or personal interest, in a more intimate fashion than the royal examples already described, and even than those having an armorial shield or two !n prominent parts. They have something more personal to show ; in a humbler fashion they may be compared to that at Bruges, which tells its tale in an inimitably grand way.

These “storied” chimneypieces form quite a delightful class. Take, for instance, that celebrated one at Speke Hall, belonging to the year 1564. The overmantel is broad, but rather low, and divided into panels by dainty carved pilasters. On the frieze painted canvas was stretched, giving the pedigree of the Norris family, In the centre panel a family party was rudely carved. William Norris and his two wives (as a matter of fact he married them successively in the orthodox fashion) sat behind a table, while their nineteen children stand in front Other figures were carved on the side panels.

Then at Bailieborough, Derbyshire, we find a handsomely carved stone chiinneypiece, having coupled Corinthian columns with fluted shafts supporting the lintel; above are two richly carved pedestals on which stand two caryatides, one representing Justice. Now the owner, Rodes. was a Justice of the Common Pleas. Three shields bear respectively his own arms and those of his two wives. Of the heraldic variety we have a good example at Haddon Hall, Derbyshire. It is in the Great Hall, and specially designed to impress visitors.

The arms of the builder, Bess of Hardwick, Countess of Shrewsbury, appear in a lozenge, crowned w ith a coronet and supported by two rampant greyhounds. Curiously enough, in spite of the shield being enbigned with the Countess’s coronet, the bearings are her paternal arms, which piece of heraldic incongruity is quite characteristic of that vigorous dame. The arms are a beautiful piece of work, strongly carved. Unfortunately, the blending with the surround. is not so happy as is usually the case with Tudor treatment. The drapery on the outside scroll with small medallions, and the small swags with pendant fruit in the frieze, distract the attention, though the use of the cartouche is excellent. In the same house there is another colossal structure about 18 ft. high by 12 ft. wide. It is of white and coloured marbles, rather severely treated, there being little ornament except the circular frame and statue in the centre of the overmantel.

Two interesting examples of the use of plaster are to be seen respectively at Little Moreton Hall, Chester, and at Plas Mawr, Conway. In the former case the fireplace is deeply recessed, and is framed with carved walnut pilasters, with foliated capitals; the lintel frieze is also decorated with folinge conventionally treated. Above this is a shelf with elaborate mouldings, supporting two crudely moulded plaster figures of Justice and Science, standing on pedestals. The central panel, with egg moulding, contains a quartered shield surrounded by lambrequin. The frieze and cornice are well moulded and highly decorated. At Plas Mawr the fire¬place m the entrance hall is surrounded by a stone framing, the broad, straight lintel being composed of large stones, curiously joggled, the stones being cut alternately with two large semi-circular swellings at the sides, and with two corresponding depressions. It gives the impression of a balustrade. The overmantel in plaster is of a particularly elaborate character. There are six quite graceful termini, five coats-of arms, a lion, and a crowned fleur de lys, besides floral decorations. In the drawing room above a similarly rude stone framing is some fine plasterwork, the centre panel being framed by two termini supporting a carved cornice. The panel contains, moulded in plaster, a Tudor rose within a Garter, and the letters FI.R. The details of the plasterwork blend with the similar treatment of the walls. In Queen Elizabeth’s Room we see a stone fireplace with little moulding and hardly any projection, and above the lintel a pro¬jecting chimney breast of plain plaster carried straight up to the ceiling. These are dated 1580. At Wroxhall Manor House, Wiltshire, there is an elaborately carved stone fireplace of Renaissance design. It has two pairs of female termini, nude to the waist. On the architrave are niches sheltering small allegorical figures. At Loseley Hall, near Guildford, we have a remarkable carved stone specimen, where the struggle between the Gothic and Renaissance is rather two apparent. It belongs to the year 1562, is in the dining-room, and is 13 ft. b in. high and proportionately broad, though with but small projection. The jambs are decorated with lions’ masks, with swags of flowers and leaves in their mouths. These are flanked by coupled Corinthian columns, with acanthus capitals. Shaw gives particulars of an oak chimney- piece that existed ife the drawing-room of a house built in 1596 on the Yarmouth Quay. It was well designed, simple in outline, but with elaborately carved decorations. Coupled Corinthian columns supported the lintel and shelf, and above these were termini, ending in foliage, supporting classic ornaments symbolising Commerce and Plenty. The caduceus of Mercury is cleverly combined with cornucopias in such a way as to form an anchor. The upper part was divided into three compartments, surmounted by a frieze and cornice. At a later period the central panel was filled with a well designed coat-of- arms of James I., carved :n high relief. A more ornate structure was put up at Combe Abbey, Warwickshire, tradition says by Lord Harrington when he was about to receive the Princess Elizabeth under guardianship. It s a rectangular con¬struction, of fair projection, reaching from floor to ceiling, broad and with liberal square opening. Though the classic in-fluence :s seen especially in details of the architrave, the lower columns are of the fancy shaped, diminishing order, much deco¬rated, while the whole is covered with broad strapwork. In the centre panels are the arms of Henry VIII., with the Red Dragon of Wales as one of the supporters, carved on a big scale in high relief. An equally marked duality .s seen in the Great Gallery at Burton Agnes, Yorkshire. The chlmneypiece, which measures about 7 ft. by 5 ft., has a deeply recessed fireplace framed with carved stone, surrounded and topped by carved wTood. The handsome frieze is supported by well formed pilasters, and above them are canephori, the baskets of fruit, flowers and leaves beirg unusually well proportioned, placed under a projecting cornice. The panels are carved with figures of Honour, Faith, Hope, Charity, and Pandora, surrounded by floral scrolls. It should be mentioned that this example stands in a gallery 115 ft. by 23 ft., high <n proportion, with a semi-circular ceiling, the whole decorated with six series of scrolls, in the form of rose branches with large leaves and blossoms. The same feeling is noticeable in the great chimneypiece in King William’s Room at Castle Ashby, Northampton. The fireplace 11 has a slight carved stone surround, the lintel hearing the arms and crest of the owner. Framing this is a carved oak overmantel, designed in two tiers, each ha\ing three nicnes sheltering figures of Pandora, Justice, Temperance Faith, Hope, and Charity. The panels are carved en cartouche tecourbde. In the panelled hall of the same mansion there is another big fireplace, with quite plain slender marble jambs and lintel, and an elaborate carved oak surround, with two termini supporting a shelf, above which are niches with Corinthian columns and shell backs, sheltering two statuettes. The central panel is filled with arabesques, and we also see an armorial shield. At the Victoria and Albert Museum there is a chimney piece of the Elizabethan era brought from Great St. Helens, City. The overmantel has panels with heavy raised mou'dings, and three carefully proportioned Corinthian columns. Another carved stone, and oak specimen from Enfield to be noted. Harrison’s reference to chimneys in England at the opening of the 16th century has been quoted at the beginning of this chapter. Although it is really outside the scope of this book to discuss the subject (one fully deserving a small monograph), it is impossible to neglect the matter altogether. We are still sadly oppressed by the tyranny of the hideous 19th century chimneypot, ugly in its nakedness, hideous when cowled; we have every reason to look back with appreciation if not with envy some 300 years or more. The treatment of the chimney shaft, stack and top, is thoroughly typical of the period and nation ; it is the outward manifestation of combining decoration with solid comfort that we see in the design and execution of the chimneypiece. They were usually built of red brick, of fine dimensions, boldly carried up, never shamefacedly masked, for they were things of utility beautified. Their number on the roofs of large Manor Houses is astonishing, only less so than the easy variety shown. At Compton Wynyates, built >n the second year of Henry VIII., and at Hampton Court Palace, we see. a great many, standing out boldly, and each one differently treated. At Hampton Court the decorations are geometrical; the bodies of the tops, under projecting cornices, are masses of tracery carried out in carved squares, diamonds, lozenges, zig-zags and wavy lines. At East Barsham the great brick chimneys are decorated heraldically, lions rampant on one, fleur dc Us on another in a trelliswork of crossed lines, all carved out of bri*;k. The tops are circular, square, octagonal, but are all treated as not inconsiderable parts of a building. Occasionally we see such daring eccentricities as at Aston Bury, with its great stacks placed on each side, and lowering above, a gabled end pierced by a dormer window. At Great Cressingham Manor House, Norfolk, we find the huge solid stacks springing from the ground floor, the octagonal sides or¬namented with recessed niches with multifoil arches, and ending in twin octagonal decorated tops. This outstanding boldness is all the more curious because with the chimneypiece itself the tendency was to reduce projection as much as possible without abandoning monumental treatment, but 'l demonstrates how practical utility was the guiding principle of the Tudor builders.